Berry and The Alexandrian Link

On his way back from a recent trip, AdventureMan bought a book in an airport, which he read and then asked me to read. Here is what he said:

“It’s not a great book, but I don’t know why I say that. It has an interesting idea and I want to know what you think.”

So just after I finished Inheritance of Loss I started in with this book, and it was the second book I will not recommend to you.

It is wooden. The characters are about a millimeter deep. The plot is unbelievable and doesn’t make sense and doesn’t hang together. It is full of adventure and travel and shoot-outs, which our “hero” miraculously comes through without a scratch while all around him his foes are dropping like flies.

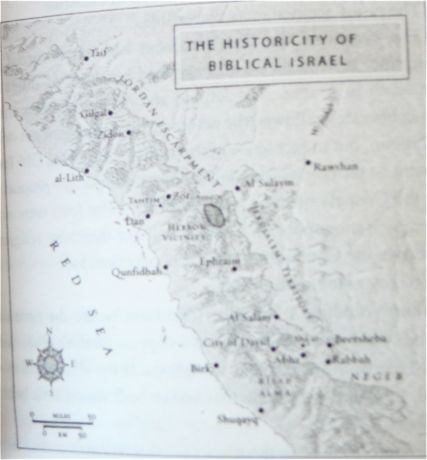

It DOES hinge on an interesting theory, one I had never heard before. There is a Lebanese historian and archaeologist, Kamal Salibi, who published a book called The Bible Came from Arabia. In this book Salibi makes his case for the “holy land” which was given to Abraham not being in Palestine at all, but rather in what is currently Saudi Arabia, along the western coast. He uses the utter lack of archeological findings in current day Israel/Palestine which support biblical accounts, and the plentitude of place names in the Asir region which closely resemble what the place names would have looked like and sounded like in ancient Hebrew, the language of the earliest biblical times.

The book, and the theory was, of course, controversial. If the contentions were true, it would undermine the foundation of the state of Israel in Palestine; it would mean that people have been fighting for the last 60 years over the wrong piece of land.

Here is a (very bad) photo of the map in the book which shows where Salibi believes the biblical cities were actually located. He believes “Jerusalem” was not a city, but an area within which were several cities. He believes “the Jordan” was not a river, but a mountain range, and that here, also, Moses and his refugees from Egypt wandered.

Unless you really love reading badly plotted books with cardboard characters, I would not recommend reading The Alexandrian Link. As a jumping off point for an interesting line of research – AdventureMan was right; this book gives you something new and different to contemplate.

Inheritance of Loss

Most of the time, if I don’t like a book, I won’t even bother telling you about it. This book, The Inheritance of Loss, by Kiran Desai, is an exception for one reason – it IS worth reading.

Inheiritance of Loss showed up on the book club reading list for the year, and I ordered it. I read the cover when the book came, and it didn’t sound that good to me, so I read other books instead. The next time it came to mind was when a friend, reading the book, said she was having trouble with it, and asked me if I had started it. This friend is a READER, and a thinker. It caught my attention that she would have problems reading a book, so I decided to give it a try.

This is a very uncomfortable book. The characters live in the shadow of the Himalayan mountains. The most sympathetic character is a young orphaned girl, sent to live with her grandfather. With each chapter, we learn more about all the characters, how they came to be here, what they think, what their lives have looked like.

The author of this book has a very sour look on life. She has snotty things to say about every character. You can almost feel her peering around the corner, eyes slit with evil intent. She is that vicious neighbor who comes by and never says anything nice about anybody, and when you see her talking with your neighbor, you get the uneasy feeling she could be saying something mean about you, and she probably is.

The book covers a wide range of topics – Indian politics, Ghurka revolts, English colonization, Indian emigration to the US and UK, everyday vanities and pride in petty things, how people destroy their own lives, how people can be cruel to one another, oh it’s a great read (yes, that is sarcasm).

At the same time, this vicious unwelcome neighbor has a sharp eye for detail. You may not like what she is telling you, but you keep listening, because you can learn important tidbits of information from her. In my case, I learned a lot about how life is lived in a small mountain village in India, the struggles of illegals in America and how class lines are drawn, ever so finely, when people live together. I learned a lot about the legacy of colonialism, and the creep of globalization. This unwelcome neighbor has a sharp tongue, always complaining, and yet . . . some of her complaints have merit.

I don’t believe there was a single redeeming episode in the book. There was not a paragraph to feel good about. I am glad to be finished with the book – but, yes, I finished it, I didn’t just set it aside in disgust, or give it away without finishing.

Here is the reason I am telling you about this book – as uncomfortable as this book is to read, I have the feeling, upon finishing, that ideas and images from this book will stick with me for a long time. I have the feeling that it contributes to my greater understanding of how things work, how people think differently from other people, and on what levels we are very much the same.

Here is an excerpt from the book, at a time during which the Judge is a young Indian, studying in England:

The new boarding house boasted several rooms for rent, and here, among the other lodgers, he was to find his only friend in England: Bose.

They had similar inadequate clothes, similar forlornly empty rooms, similar poor native’s trunks. A look of recognition had passed between them at first sight, but also the assurance that they wouldn’t reveal one another’s secrets, not even to each other.

. . . Together they punted clumsily down the glaceed river to Grantchester and had tea among the jam sozzled wasps just as you were supposed to, enjoying themselves (but not really) as the heavy wasps fell from flight into their laps with a low battery buzz.

They had better luck in London, where they watched the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace, avoided the other Indian students at Veeraswamy’s, ate shepherd’s pie instead, and agreed on the train home that Trafalgar Square was not quite up to British standards of hygiene – all those defecating pigeons, one of which had done a masala-colored doodle on Bose. It was Bose who showed Jemubhai what records to buy for his new gramophone: Caruso and Gigli. He also corrected his pronunciation: Jheelee, not Giggly. . . .

This it was that the judge eventually took revenge on his early confusions, his embarrassments gloved in something called “keeping up standards,” his accent behind a mask of a quiet. He found he began to be mistaken for something he wasn’t – a man of dignity. This accidental poise became more important than any other thing. He envied the English. He loathed Indians. He worked at being English with the passion of hatred and for what he would become, he would be despised by absolutely everyone, English and Indians both.

I consider this a review, and not particularly a recommendation. I read the book, I finished the book and I learned from the book. I didn’t like the book. I recommend it only as a challenge, for people who like to read and stretch their minds in new directions.

Morning Grin

A woman went to a walk-in clinic, where she was seen by a young, new doctor. After about three minutes in the examination room, the doctor told her she was pregnant.

She burst out, screaming as she ran down the hall. An older doctor stopped her and asked what the problem was, and she told him what happened. After listening, he had her sit down and relax in another room.

The doctor marched down the hallway to the back where the first doctor was and demanded, “What’s the matter with you? Mrs. Terry is 59 years old, has four grown children and seven grandchildren, and you told her she was pregnant?”

The young doctor continued to write on his clipb oard, and without looking up, asked, “Does she still have the hiccups?”

Brother Odd: Dean Koontz

I’ve always liked Dean Koontz; he knows how to be compassionate and funny at the same time. When I showed books I had bought, my long-time friend Momcat said “Oh, you’re going to like that book!” and oh, how right she was. I like it so much that now I have to go back and buy the previous ones to catch me up.

The main character, whose name, to his embarrassment, is Odd Thomas, has secluded himself in a monastery in search of spiritual peace. Or was he brought here for another reason? Odd Thomas has some very odd gifts; he can see the undeparted dead, for example, and he can sense things that normal humans can’t. You would think these would be very cool talents, but Odd is in his early twenties, and his talents only serve to isolate him and make him feel a little alien.

The monastery / nunnery is a good place for him, full of very human monks and nuns, some of them very wise and very compassionate, as well as competant. It’s a good place for Odd Thomas, a healing place and a place where his strange gifts are protected by his spiritual cohabitants. The monastic life attracts a lot of people trying to put their pasts behind them to seek spiritual goals, and also attracts those with their own agendas.

The monastery is well endowed, and contains a special school for young people who have physical and/or mental disabilities. Some can learn enough to return to society, and some will probably spend the rest of their shortened lives under the safety and care of the nuns – until, all of a sudden, a threat appears, directed at the children.

Dean Koontz writes interesting books. He often includes benign animals, he often focuses on threats to women and children, and while his books are not difficult to read, neither are they something you read and easily forget. Both AdventureMan and I read an earlier Dean Koonz book, Watchers, to which we have often referred through the years, as one of his characters ends up homeless and living in a car with her son. She talks about money just giving you more options, and about those who are one paycheck away from homelessness. It was an easy read, but he includes some tough ideas, things you find yourself mulling over even years later. That’s a good read in my book!

The only problem with this book was that it was so good I finished it in one flight. Good thing I had packed a back-up book in my carry-on!

Picoult and My Sister’s Keeper

I don’t know where I got the idea that Jodi Picoult wrote girly books, maybe because when you go to a bookstore there are so many of them? I just assumed they were romance and passed right by until several months ago, in a small used book store, I found one that was in the book club section, and those are usually pretty good reads. I bought it, but put off reading it, assuming it was an easy read, maybe I would read it on an airplane one day.

For some reason I moved it up, maybe I had heard a review or something. It moved to the bedside group, the “in line for immediate reading” group. At a time when we were particularly busy, I finished my other book and this was next, and I thought “Oh well, yes we are busy, but this will be light reading.”

I couldn’t have been more wrong.

This book, My Sister’s Keeper, is not light reading. It is a book a lot like We Need To Talk About Kevin one of the most terrifying and unforgettable books I have ever read. It is a book about motherhood, and parenting and tough choices. It is a book about how sometimes your entire life is yanked, and all the focus is on one area, to the detriment of others. It is a particularly tough book if you are a mother.

The main character, Anna, was conceived so that her stem cells, from the umbilical cord, will be used to help her sister, Kate, who has leukemia. Family life is chaotic, to say the least, as the vigilant parents’ attention is constantly on Kate, who suffers frequent relapses.

Picoult uses the voices of Anna, Kate, Jessie – the brother, a pyromaniac, Brian (the father), Sara (the mother), Campbell (Anna’s lawyer) and Jesse (Anna’s guardian ad litem) to tell the story.

Anna has approached Campbell, a lawyer, to achieve medical emancipation. She loves her sister, she has shared a room and her entire life with her sister, she has given stem cells, she has given bone marrow, she has been through several medical procedures to keep her sister’s cancer in remission, but at 13, she balks when expected to give one of her kidneys is a last ditch attempt that even the doctors have little expectation will succeed. She hires a lawyer.

Sara is a mother you would love to hate. You would love to grab her by the shoulders and say “Pay attention! You have THREE children, and two of them need your attention, too!” but something holds you back, and that something is the serious doubt you have about how you would handle the same situation. In extreme circumstances, people make the best choices they can, and when you are in extreme circumstances day after day, things start to fray, and then they start to fall apart. This family is past the fraying part, and we hold our breaths hoping they won’t fall apart.

It’s not a hard read because of the technical terms; this is a book where a 13 year old knows all the vocabulary of cancer, and we learn it, too. It flows naturally in the book.

Kate has acute promyelocytic leukemia. Actually, that’s not quite true – right now she doesn’t have it, but it’s hibernating under her skin like a bear, until it decides to roar again. She was diagnosed when she was two; she’s sixteen now. Molecular relapse and granulocyte and portacath – these words are part of my vocabulary, even though I’ll never find them on any SAT. I’m an allogeneic donor – a perfect sibling match. When Kate needs leukocytes or stem cells or bone marrow to fool her body into thinking it’s healthy, I’m the one who provides them. Nearly every time Kate’s been hospitalized, I wind up there, too.

None of which means anything except that you shouldn’t believe what you hear about me, least of all that which I tell you about myself.

Aha! We are reading a book with an unreliable main character!

It is a hard read because we all have families, and we all face tough decisions. There is a part of us that says “thank God we are not in this situation” and another part that says “there but for the grace of God . . . ” It is a tough book because we don’t know who we will become when life-changing circumstances hit us, we don’t know what choices we would make, because we are afraid, and because we don’t want to find out.

There are some surprises, though, and you will want to keep reading. There is a lot of love here, in the cracks between the tragedies. My Sister’s Keeper has three sets of sisters, and a lot of focus on that very special relationship. The men, too, come off well at the end.

Not an easy read, but a book that will stay in your heart for a long time.

Iznik Tiles, God whispers . . .

OK, OK, now you are going to see my ditzy side. I remember my mother visiting, and I was telling her what my cat was saying. She gave me one of those long, considering looks, and then said “I hope you don’t talk this way in front of other people. They might think you are a little crazy.”

I guess we all have crazy thoughts, fantasies. I kind of think cats have a very simple kind of telepathy; they can, I think, pull images out of your head. They are simple creatures, but ones we don’t fully understand. Am I crazy for thinking that?

And that has nothing at all with this blog entry, except to warn you that sometimes I am not entirely rational, I can be fanciful.

Two books in a row I have most recently read referred to Iznik tiles. The first was a Donna Leon book Death in a Strange Country where a woman who lives very frugally, even on the edge of poverty, sits in her run-down Venetian apartment surrounded by masterpieces of world art, including Iznik tiles.

The second book, which I just finished, is The Janissary Tree by Jason Godwin, in which his detective Yashim Togalu, a eunuch in the early post-Janissary Ottoman Empire, notes the Iznik tiles in the great receiving room of the Sultan.

To me, when two books in a row refer to the same tiles I have never heard of, it is like a little whisper from God saying “look this up.” It may be that I don’t even need this information, maybe I am just supposed to pass it along to YOU! I don’t know.

I DO know I am glad I looked it up. I love blue and white. I love intricate, curved design. And oh WOW, I love Iznik tiles and pottery.

“In the late 16th century the tiles of Iznik incorporated new designs and new colors and Iznik immerged as the preeminent city for tile production in the Ottoman empire. A major part of the transformation had to do with the introduction of Persian designs rendered in a distinctly Ottoman style.” From Guide to Iznik Tile and Plates.

In case you want to know more, this is an excerpt from Nurhan Atasoy’s Article on Iznik Tiles:

The finest Iznik pottery was produced during the reign of Suleyman the Magnificent and up to the end of the 17th century.The tiles and other pieces were exuberantly decorated with hyacinths, tulips, carnations, roses, and stylised floral scrollwork known as hatayi, Chinese clouds, imbrication, cintemani (a design consisting of three spots and pairs of flickering stripes), and geometric patterns.

The Turkish Ministry of Culture proclaimed 1989 as Iznik Year, and numerous events and activities relating to Iznik pottery were held. Iznik has a special place in the history of Turkish art, and thanks to the efforts of Turkish Airlines and Turk Ekonomi Bankasi Iznik Year became Iznik Years. Researchers are continually discovering more about e beautiful type of ceramics, whose designs are enjoying a new wave of popularity.

And here is a source from which you can order your own Iznik tiles: Yurdan.com.

There is no socially redeeming value to this post. Only that I learned something, and discovered something which is, to me, breathtakingly beautiful. One source says Iznik tiles were made of quartz, which gave them a great elasticity when exposed to varying degrees of heat and cold, which I find fascinating in that today the hottest new countertops are done in quartz. I think Adventure Man and I need to visit Iznik, the ancient Nicea, and take a look, don’t you think? I would love to see more of these tiles, in person, maybe somewhere I could touch them. 🙂

Donna Leon: Wilful Behavior

You think Donna Leon is writing about one thing, and then you discover it is about something else entirely. It seems to happen often in that line of work – you see the same thing on Law and Order, and Cold Case, and The Wire – what initially seems like a straightforward crime had depths and switch-backs unfathomable from the initial crime scene.

In Wilful Behavior, Paula, Brunetti’s wife, has just about had it with her university level students. They have no yearning for knowledge and insight, they are rife with materialism, she is feeling burned out and cynical. One student, who bucks the trend, comes to talk with her, and then Brunetti about the possibility of a post-mortem clearing of a person’s name, but she won’t give the name of the person or the crime that person committed. Before Commissario Brunetti has begun to plumb these depths – the student is murdered.

It’s always depressing when a young person dies. You can’t help but think of how treasured they were, how full of potential, and all that is gone now, wasted. A light in the world has gone out, and you grieve for how brightly that light might have shown. Brunetti and his wife only knew the murdered girl briefly, but her murder strikes them deeply.

Here is an excerpt from Brunetti’s discussion with the student before she was killed:

“I didn’t know young people even knew who Il Duce was.” Brunetti said, exaggerating, but not by much, and mindful of the almost total amnesia he had discovered in the minds of anyone, of whatever age, with whom he had attempted to discuss the war or its causes. Or worse, the sort of cock-eyed, retouched history that protrayed the friendly, generously disposed Italians led astray by their wicked Teutonic neighbors to the north.

The girl’s voice drew him back from these reflections. “Most of them don’t. This is old people I’m talking about. You’d think they’d know or remember what things were like then, what he was like.” She shook her head in another sign of exasperation. “But no, all I hear is that nonsense about the trains being on time and no trouble from the Mafia and how happy the Ethiopians were to see our brave soldiers.” She paused as if assessing just how far to go with this conservatively dressed man with the kind eyes; whatever she saw seemed to reassure her, for she continued. “Our brave soldiers come with their poison gas and machine guns to show them the wonders of Fascism.”

So young and yet so cynical, he thought, and how tired she must be already of having people point this out to her. “I’m surprised you aren’t enrolled in the history faculty,” he said.

“Oh, I was, for a year. But I couldn’t stand it, all the lies and dishonest books and the refusal to take a stand about anything that’s happened in the last hundred years.”

“And so?”

“I changed to English Literature. The worst they can do is make us listen to all their idiotic theories about the meaning of literature or whether the text exists or not.” Hearing her, Brunetti had the strange sensation of listening to Paula in one of her wilder moments. “But they can’t change the texts themselves. It’s not like what the people in power do when they remove embarassing documents from the State Archives. They can’t do that to Dante or Manzoni, can they?” she asked speculatively, a question that really asked for an answer.

“No,” Brunetti agreed. “But is suspect that’s only because there are standard editions of the basic texts. Otherwise, I’m sure they’d try, if they thought they could get away with it.” He saw that he had her interest, so he added, “I’ve always been afraid of people in possession of what they believe is the truth. They’ll do anything to see that the facts are changed and whipped into shape to agree with it.”

And, as it turns out, in the persistent corruption of Venetian bureaucracy, that is exactly what this murder is all about – the theft and possession of art during WWII, and how the ramifications are still trickling down today. How people are willing to kill to keep the past safely in the past, and to hang on to their treasured and priceless possessions.

Donna Leon continues to be one of my favorites because she is never formulaic – she has ISSUES, and she uses her Brunetti novels to educate her readers. As we become educated, we continue to experience Venice through all the senses, the smell of the veal cooking for dinner, the taste of the tiny espressos in the corner cafe meeting places, the gruesome murder sites, the sound of the waves in the canals, whipped up by the prevailing winds . . .you read Donna Leon, you become Venetian.

A Thousand Splendid Suns

Once I picked up Khaled Hosseini’s A Thousand Splendid Suns, I barely put it down again until I was finished. I found myself thoroughly involved in the lives of Mariam and Leila, unwilling even to stop to fix dinner! The author of Kiterunner has hit another home run.

There was a time when we would listen to older state department types talk – with enormous longing – about their tours of duty in Afghanistan, pre-Soviet invasion, pre-Taliban, pre-American occupation. Have you ever read James Michener’s Caravan? There are two countries I long to vist, but the countries they are now are not the countries I heard people talk about – Afghanistan and Ethiopia. Our friends loved their times in these two countries.

A Thousand Splendid Suns opens in a small village outside Herat, and then takes us to Kabul. Mariam is born harami, a bastard, of a village cleaning woman in the house of a very wealthy man. Her father builds a small hut for her mother and herself in a remote part of the small village, and visits Mariam every week. Life is simple, and difficult, but also full of kind people who visit and who are concerned with Mariam’s welfare.

After marrying, Mariam goes to Kabul and learns a new way of life with her husband, Rasheed. What fascinates me with Hosseini is that while Rashid is one of the villians of this novel, he is just a man, doing the best he can given his own upbringing and limitations. In a sense, he is “everyman”, the strutting, domineering, sometimes brutal and abusive husband we find in every culture. But Hosseini also gives him transient bouts of kindness which blow through a little less often than the transient bouts of cruelty.

He also gives us good men, in this book, in the person of Jalil, the father of Mariam, who steps up to the plate in acknowledging Mariam and supporting her and her mother, but fails to nurture in the very real way women need nurturing from their fathers in order to reach their full potential in life. Hosseini also gives us a very strong man in the book, Tariq, who, although he has only one leg, is more wholly a man than any other man in the book. I imagine that this is not unintentional. (How Kissingerian is that for a double negative?!)

Written almost entirely in the Afghan world of women, we see through the eyes of Mariam, and later Leila, the transitions in Afghanistan and their impacts on daily life. We experience happiness with them, and peaceful scenes in quiet moments, raising the children, stepping outside into the garden at night to share a cup of tea and a shared bowl of halwa.

Between the moments of peacefulness, we also experience incoming morter rounds, explosions, marauding bands of warlords, and starvation. We go into a women’s hospital under Taliban control, where there are no medications, no running water, no instruments, and an Afghani female doctor does a C-section with no anaesthesia and is required to keep her burqa on. We watch a mother abandon her role and take to her bed when her two sons are killed fighting the Soviets, we experience betrayal and we experience helplessness, and we experience a Kabul women’s prison. A Thousand Splendid Suns is a rich feast of experiences, juxtaposing the everyday chores of women around the world – cooking, raising children, laundry – with events on the world stage.

(Available from Amazon for $14.27 plus shipping.)

Peter Bowen: Wolf, No Wolf

“You have to take this. You’ll really like it,” Sparkle insisted as I inwardly groaned, thinking of the TWO stacks of unread-must-reads by the side of my bed, and my already bulging suitcases.

“I know it doesn’t sound like something you’ll like,” she went on, slightly frustrated with me, with herself, “but once you start reading, you’ll get into it.”

Not exactly a ringing endorsement, but good enough for me. I always KNOW what I think she will love, and she has done me many a favor in return, introducing me to authors and series worth reading.

“It’s about Montana. The main character is mixed Indian and French and some other things, a grandfather, and it all takes place in a small town in Montana . . . ” she sort of fizzles out. “I’m really not doing a very good job of making this interesting.”

And she sighs in frustration.

So, about a month later, just because I love my sister, I pick the book up and start reading while waiting for my husband to get home for dinner. As it turns out, he is very very late – and I am very very glad. I don’t want to stop reading!

When you first jump into Wolf, No Wolf by Peter Bowen, it takes you a minute to adjust your ear to the way they talk. These aren’t people most of us have met before. Gabriel DuPre´ is m´etis, a mixed blood. His ancestors are French who came early to the great continent that is now the US, Canada and Mexico, and they trapped and hunted, married native American wives, and developed a culture all their own. His language pattern is similar to that of the Cajun in Louisiana.

He is a cattle brand inspector in this small Montana town. His children are grown, he has so many grandchildren he can’t remember all their names. Every now and then, he pins on his deputy sherrif badge to solve a mystery in the small town of Toussaint, Montana.

Here is how Wolf, No Wolf opens:

Du Pre´ fiddled in the Toussaint Bar. The place was packed. some of Madelaine’s relatives had come down from Canada to visit. It was fall and the bird hunters had come, to shoot partridges and grouse on the High Plains.

The bird hungers were pretty OK. The big game hunters were pigs, mostly. The bird hunters were outdoors people; they loved it and knew it, or wanted to. The big game hungers wanted to shoot at something big, often someone’s cows.

Bart had bought a couple thousand dollars’ worth of liquor and several kegs of beer and there was a lot of food people had brought. Everything was free.

Kids ran in and out. The older ones could have beers. Bart was tending bar. Old Booger Tom sat on one of the high stools, cane leaned up against the front of the bar.

“You do that pretty good for someone the booze damn near killed,” said Booger Tom. “I know folks won’t be in the same room with the stuff.”

“Find Jesus,” said Bart. “It’s not too late to save your life.”

He went down to the far end of the bar and took orders. Susan Klein, who owned the saloon, was washing glasses at a great pace.

One of Madelaine’s relatives was playing the accordion, another an electric guitar. They were very good.

Du Pre´ finished. He was wet with sweat. The place was hot and damp and smoky, so smoky it was hard to see across the room. The room wasn’t all that big, either.

Madelaine got up from her seat, her pretty face flushed from drinking the sweet pink wine she loved. She threw her arms around Du Pre´ and kissed him for a long time.

“Du Pre´,” she said, “you make me ver’ happy, you play those good songs.”

. . …

Someday this fine woman marry me, thought Du Pre´, soon as the damn Catholic church, it tell her OK, your missing husband is dead now so you can quit sinning, fornicating with DuPre´.

I’ve never hung out in a bar in Montana, fiddled, or had a girlfriend named Madeleine (!), but already I feel like I know these people and this life. Peter Bowen is the Donna Leon of Montana, introducing us to the kind of crimes that happen in those sleepy looking towns we drive past on the superhighways, glancing at, or stopping to fill our gas tanks.

DuPre´ is a good man, and, like many a good man, sometimes has to do a bad thing to protect those he is sworn to protect. Policing is not pretty business.

The first story has to do with the re-introduction of wolves back into the Montana highlands, something not at all popular with those who have been raising cattle there. The second book in this two-book collection has to do with serial killers, how they stay under the radar, and how very difficult it is to catch them.

In both books, it is as much about a new way of living and thinking as it is about solving the crime. DuPre´ consults often with his friend Benetsee, the local medicine man, who sees things we don’t see. One of the FBI Agents is Harvey Wallace, also more than half native American, whose real name is Harvey Weasel Fat. The books are about how men and women fight, the nature of male friendships and female friendships, and very much about the human condition wherever we may be.

Life is short. I can never live in all these places long enough to even scratch the surface of the flavor of each variety of life. But these books help, they give us glimpses into another way of thinking, another way of doing things, and stretches our little minds just a little so that we learn to think more flexibly.

So who is going to write the Kuwait detective series? Who will take us into the diwaniyyas seeking information, who will take us out on the shoowi to gather information against those delivering drugs to Kuwait, with whom will we camp in the desert, avoiding explosives left over from the Iraqi invasion? I think his name is Anwar al Kout (the light of Kuwait!) and his wife is Suhail (the Yemeni Star!) – somewhere out there is someone who can take us into Kuwait and bring it alive. Where are you?

(You were right, Sparkle. I loved it!)

Burke and Tin Roof Blowdown

“So what are you reading?”

Sparkle’s question didn’t surprise me. It’s one of the things we share, a love of reading, anything really but especially mystery books.

“I just started James Lee Burke’s new book, The Tin Roof Blowdown,” I responded.

Her eyes brightened and she threw back her head and laughed! “I knew it! I saw he had a new book out and I hoped you had already bought it!”

What she’s not saying is “bought it, read it and will pass it along to me!”

It’s what we do. I am in the middle of a series she recommended and loaned to my son, he is 3/4 way through (the Hyperion series) and has passed along the first two volumes to me, which, when finished, I will return to my sis.

James Lee Burke’s newest book, The Tin Roof Blowdown, is Burke at his best. His last book ended with the ominous storm rolling in that has changed the face of New Orleans and this book starts with Hurricane Katrina. The stories are heartbreaking, and all the more so because they are true. New Orleans is one of the most corrupt cities in the United States, about one third of the police force LEFT the city they were hired to protect in the evacuation, and the poorest of the poor were left behind, to suffer, to struggle to live, or to die. Many did all three.

Detective Dave Robicheaux is called into the “Big Sleazy” with the rest of the New Iberia police force to help with rescue operations, and to try to bring some order into the chaos. He gets involved with a missing priest, two looters being shot, a robbery that includes cocaine, counterfeit cash and blood diamonds, and the usual cast of psycopaths and organized crime goombahs.

The book builds inexorably to a nail-biting climax.

This author can WRITE. He is head and shoulders above the average churn-em-out detective writer. Here is one of his less poetic, but more insightful entries:

” . . . the honest to God truth is that law enforcement is not even law “enforcement.” We deal with problems after the fact. We catch criminals by chance and accident, either during the commission of the crimes or through snitches. Because of forensic and evidentiary problems, most of the crimes recidivists commit are not even prosecutable. Most inmates currently in the slams spend lifetimes figuring out ways to come to the attention of the system. Ultimately, jail is the only place they feel safe from their own failures.

Unfortunately, the last people on our minds are the victims of crime. They become an addendum to both the investigation and the prosecution of the case, adverbs instead of nouns. Ask rape victims, or people who have been beaten with gun butts or metal pipes or tied to chairs and tortured how they felt toward the system after they learned that their assailants were released on bond without the victims being notified.

I don’t believe in capital punishment, but I don’t argue with the prosecutors who support it. The mouths of the people they represent are stopped with dust. What kind of advocate would not try to give them voice?